Buttcracks, rats and gnarled cloven hoofs fit for Hell’s catwalk – Australian fashion is best when it’s scary. In a small market ripe for metamorphosis, writer Arielle Richards says the great designers are those who sidestep commercial viability to get their freak on.

For more fashion news, shoots, articles and features, head to our Fashion section.

At Australian Fashion Week in 2001, Sydney-based label Tsubi sent around 200 live rats down the runway, scandalising capital-F-fashion and forever altering the trajectory of the front row’s lives. While the RSPCA investigated the death of one rodent, regrettably flattened by a falling curtain rod, Tsubi (now Ksubi) had established itself as a changemaker – unafraid to scare off buyers, critics and consumers. It was proof a little fear in fashion is good.

But in the decades since, Australia’s biggest runways have seen less of this creative risk-taking. Any desire to effect change seems to be swallowed whole by an obvious imperative to play it safe. Well, I’ll say it: boring.

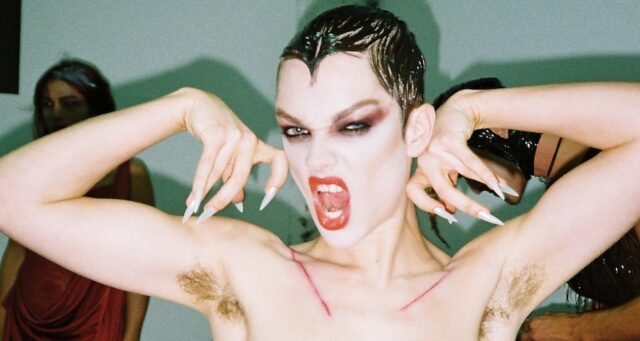

A handful of designers are challenging this. In 2024, Australian Fashion Week’s prosaic consistency was again ravaged, this time by Speed, Injury, Nicol and Ford, and Wackie Ju. The latter two presentations were both thematically subversive and aesthetically confronting: Nicol and Ford’s Thorn summoned the occult, while Wackie Ju’s collection, Saviour, explored historic colonial violence.

Thorn was inspired by Rosaleen Norton, an artist in mid-century Sydney known as the ‘Witch of King’s Cross’, who was subjugated by the press and hounded by police for her bohemian lifestyle and so-called ‘sexual deviance’. BDSM codes of whips, ropes and their implied prosthetic welts occupied one-third of the show, while the half-human-half-animal imagery in Norton’s paintings occupied another, across flouncing animal print, reptilian leathers and plumed headdresses.

For designers Katie-Louise and Lilian Nicol-Ford, whose work deals with queer and trans history, Norton’s story contained parallels to the persecution of misunderstood subcultures in present-day Australia. “I think the story of witchcraft and people living by their own rules is something that is still experienced by many minorities in Australia today,” Lilian reflects. “In a way, the show became this big, extended parable for people living on the fringe.”

Saviour, from Melbourne-based designer Jackie Wu, reimagined the 19th-century ransacking of an ancient Chinese temple by the British colony. “She had literal jump scares in the show,” says Lilian, who was among the guests. “There was a point where a model was attacked by performers hiding in the crowd. It was really very visceral, it made you feel something.”

Informed by queer politics and history, both Wackie Ju and Nicol and Ford’s shows cavorted in high fashion’s fantasy land while retaining a distinct currency – with one chopine-clad-hoof planted in community and resistance.

Matea Gluščević, a Melbourne shoemaker who custom-built pieces for Thorn, is another artist whose work pushes boundaries.She plays with preternatural forms to question the very concept of footwear. Her signature chopines – towering rocking-horse-shaped clogs dripped in kangaroo leather offcuts – propelled the artist to cult status, long before they adorned Julia Fox.

Work like Matea’s presents hope for the future of Australian fashion, says Katherine Rose, a Sydney-based stylist and creative director. Her work, under the moniker Rose Pure, heroes an ominous cast of alien, goth and juggalo references. “A lot of these emerging creatives and designers are making me feel something,” she says. “They are challenging norms and by doing so, are making an anti-fashion statement.”

Katherine points to Weilwan designer Corin Corcoran, whose work muses on trauma; Melbourne label Catholic Guilt, that weaves chainmail into luxuriant drapes; and Brisbane designer Gail Sorronda, lauded for her haunting, gothic style. I’d add the devious fetishwear-inspired garments by Pigsuit that ooze the fiendish filth and glamour inherent to the underground.

Scary is best, and not just in clothes. Kick in the Eye’s lustful interplay between hard and soft, spiky and tender – initially inspired by vintage fetish art – has been pushing the boundaries of jewellery design since 2018. More recently, Underground Sundae dared laud the grit of the rat in its designs, alongside discarded dummies and trash charms.

When they’re not trying to appeal to the masses, our best artists have plenty to say, and they’re not afraid to get freaky with their messaging. In doing so, they edge culture forward. “It’s making me feel hope for the industry in Australia, that fashion can be exciting again,” says Katherine.

When was the last time you felt true fear? If you’re a woman, queer or transgender person in Australia, statistically, not that long ago. This sunburnt country is a scary place. Forget the spiders and the snakes – there’s a femicide epidemic, transphobia is on the rise, and there are people with dozens of houses and thousands with none.

For those working in creative fields, there’s also a taunting fear of financial instability. Politicians want to eat the arts. They want to gobble up every working artist not on a Bank of Mummy stipend and spit the bloody mush out as a tax break for the wealthy.

stipend and spit the bloody mush out as a tax break for the wealthy.

Scary times. And in tough times for artistry, a big, gluttonous, homogenous bubble of commercial viability threatens to suffocate our emerging talent. “The market and consumers are scared of things outside the norm,” says Katherine. “Everything must be safe and consumable. When it’s freakier, it’s less easy to buy into or digest, but that’s what makes it art.”

Art must be weird and off-putting because individuality is always a risk. The bulky engine of capitalism crushes outliers first. It sucks out all the life and colour in the name of commercial viability, that cloaked sickle-wielding figure known to follow subversive artists around until they succumb to liquidity, or worse, ready-to-wear florals for spring. Or, they move overseas.

“I think Australia is pretty comfortable with the idea that artists in the fashion space have to go overseas to make a name for themselves,” Lilian says. “We’re very grateful and proud to be working in a generational group of designers who really want to create change here. I suppose the fear is that there won’t be enough change to accommodate all the artists who want to be creating in this space.”

Keeping the Nicol-Fords in Australia is the fact that they aren’t “necessarily” commercially driven, a freedom they acknowledge allows them to work in an avant-garde realm. “We’re not there to sell clothing. We’re there to contribute to discourse and challenge what can be done in these spaces. “We’re very comfortable with people feeling uncomfortable with our work or hating our work,” Lilian says. “At least they’re feeling something,” adds Katie-Louise.

As Katherine puts it: “Humans are freaks! Australia has a dark history. We have creative forms like fashion, art and music to explore these themes, to help express ourselves and connect with others.”

Good art forces us to confront the darkness, the shade that underpins the false harmony of our postcolonial democracy. And discomfort offers a learning opportunity, if we allow it. The Australia I know is not safe, nor is it polite. It does not toe the line of acceptability and it certainly doesn’t give a shit.

If art is both a reflection of culture and a challenge to the status quo, then Australian fashion needs to get scarier. Contort the body, subvert the ‘desirable’ form, revel in the abject horror of existence. Outside the realm of ‘normal’ is where Australian fashion is at its best.

This article was originally published in Fashion Journal issue 197.

To explore the work of Nicol and Ford, head here.

This article Hear me out: Australian fashion is best when it scares you appeared first on Fashion Journal.

2025-05-13 05:01:00

#Hear #Australian #fashion #scares

Source link